Chapter 2: How the CIA Maps the World

Among all the global maps in circulation in the United States today, one has special status: the CIA's map of the world. Endorsed by the government, handsome in design, comprehensive in coverage, regularly updated, and (most seductive of all) free to download, this digital map can be readily accessed on the website of the Central Intelligence Agency.

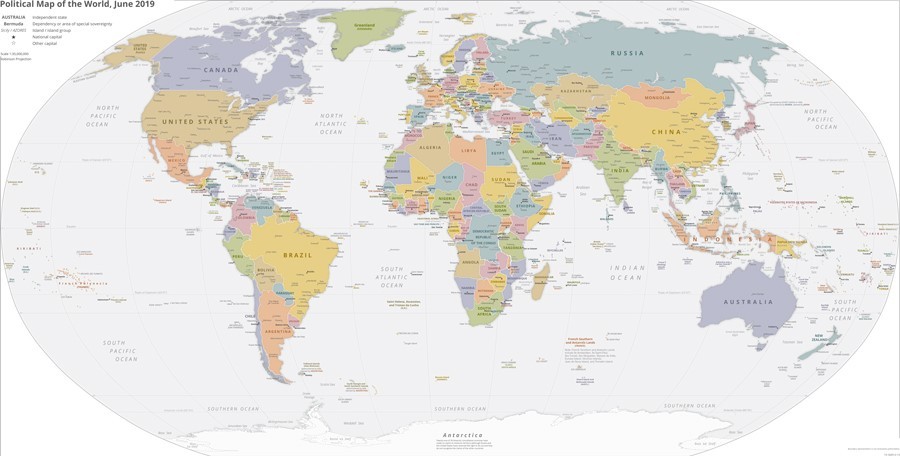

At a glance, what this world-image conjures is an attractive vision of a stable international community, with sovereignty and representation for all. How exactly does it do this? For starters, the Agency's (anonymous) cartographers, like almost all their contemporary counterparts, divide the land area of the globe into brightly colored blocks that snap together cleanly at their borders. While obviously differing in size, these units are all depicted in the same way, implying that they are all the same species of thing: independent countries (or, in popular short-hand, nation-states). With just a few exceptions, generally noted in fine print, each territory shown is a sovereign state with voting rights in the United Nations General Assembly.

On closer inspection, to be sure, a few anomalies crop up. The CIA does not actually depict all its puzzle-pieces as polities of the same kind, nor do all of them have seats in the UN. Small-font labels signal a two-level hierarchy, distinguishing sovereign states from dependencies. Most dependencies are too small to be readily visible on the world map, and only become legible when one zooms in or looks at the more detailed regional maps found on the same website. We will look more closely at formal dependencies toward the end of this chapter, after considering a number of other geospatial categories that go unmarked altogether.

One reason for delivering an extended critique of the CIA world map is straightforward. Having seen how this document is routinely handled—cited and reproduced as if it simply translated an agreed-upon international order into visual form—we are convinced that a sustained critical conversation about its premises is overdue. To jump-start that conversation, the present chapter is structured as a guided tour of sorts, alighting on a succession of places where the contours of power on the ground belie the picture on the page. We begin with de jure countries that appear only on the map, followed by de facto governments that appear only on the ground. Zones of contested sovereignty come next, including a handful that are shown as well as more that are hidden. While scores of borders around the planet are contested, only a few of those conflicts surface on the CIA map—and when they do, the signaling is often ambiguous. Finally, we consider entities that exercise territorial control without taking the form of sovereign states. Whether colonial remnants or military installations, these areas of para-sovereignty barely get a cartographic nod.

All of these slippages and oversights are well known to regional specialists, journalists, and activists. What has been missing until now is a thorough-going critique of the map as a whole: a comprehensive overview of the anomalies that have accrued to it over time, and an assessment of the cumulative challenge that they represent to its image of the international community. Proceeding from presence to absence, we begin with visible puzzle-pieces that are not quite what they seem.

Some of the most striking anomalies in the CIA world map today are a product of inertia. Although the map is annually revised in minor ways (and occasionally in major ways, when newly recognized countries are ushered into the UN), the geopolitical model on which it is based is essentially stuck in the post-WWII settlement and the subsequent decolonization movement. A lot has happened in global geopolitics since then, but those changes have been only selectively sanctioned by the U.S. diplomatic establishment. As a result, by the early twenty-first century, a number of countries on the CIA map could no longer claim the integrity that they once took for granted.

Consider Somalia and Yemen. In the terms of political scientist Robert Jackson, both today are "quasi-states" that have lost control over most of their putative territory. While it is theoretically possible for Somalia or Yemen to experience a renaissance in the coming years, that scenario seems unlikely. Somalia disintegrated decades ago, at the end of the Cold War in 1991; since then, most of its territory has been under the control of ever-shifting separatist groups, clan leaders, and Islamist insurgents. Yemen fell apart more recently, but its situation is equally fluid. At the time of writing, Yemen's nominal territory was effectively divided among half a dozen factions: Houthi rebels (backed by Iran), the Hadi-led government (backed by the Saudis), a secessionist Southern Transitional Council (supported by the United Arab Emirates), and various tribal coalitions and Islamist groups, including al-Qaeda and ISIS. Nonetheless, both Somalia and Yemen continue to occupy the seats in the United Nations that were assigned to them decades ago. Likewise, both continue to be mapped by the CIA as though they controlled lands that their current governments can only dream of regaining.

Libya is another country that appears intact on the map while being wracked with conflict on the ground. Here the UN-supported Government of National Accord (backed primarily by Turkey and Qatar) vies with the so-called Tobruk Government (backed by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia), while both contend with remnant Islamists and tribal forces. Over the course of 2018 and early 2019, Tobruk surged ahead along several fronts, but it later suffered several reversals. A cease-fire brokered by Turkey and Russia in early 2020 collapsed within hours. Many observers think that the Tobruk government's leader, Khalifa Haftar, is committed to a military solution, hoping to reunify the country on his own terms. If that were to happen, Libya might once again assume the shape it occupies on the CIA map—albeit by contravening UN designs.

Or consider Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. All three are cleaved by governmental rivalries that remain invisible in the cartography of the CIA. In Iraq, the Kurdish northeast remains a land apart, its people overwhelmingly devoted to independence and its military force, the Peshmerga, refusing to take orders from Baghdad. In Afghanistan, much of the country is under the control of a resurging Taliban, while a small area in the northeast is held by ISIS and its allies. In Syria, ISIS has essentially been extirpated, and although other Islamist groups in the interior northwest hold substantial territory, their days seem numbered. But Turkey maintains its own zones of occupation in this area, confounding hopes for unification. More significant, northeastern Syria seems firmly detached from the rest of the country. Outside the Turkish "security belt," the northeast is still controlled by Kurdish-led forces who have declared the de facto autonomous area of Rojava. Rojava is governed under quite different principles from the rest of Syria: an unusual amalgam of libertarian-socialist principles (originally espoused by Brooklyn-born Murray Bookchin) with the Kurdish feminism (jineology) of Abdullah Ocalan (the jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers' Party). Considering the Kurds' military prowess—theirs was the primary force that defeated ISIS in Syria—it is unlikely to be vanquished any time soon by the Assad regime. Rojava's leaders advocate a united Syria governed under their own framework of socialist decentralization, a vision that effectively precludes accommodation with the Damascus regime.

A handful of other countries have serious gaps in their territorial sovereignty that the CIA map similarly passes over. Consider the interior of Africa. Central African Republic (C.A.R.) is a large but notoriously weak state, roughly half of whose lands lie beyond the scope of its struggling government. As of 2019, ten percent of the population had been internally displaced, while another fifteen percent languished in refugee camps beyond its borders. If the CIA were to publish an empirically accurate map of territorial control in C.A.R., its lawless zones and refugee encampments would need to be marked. Neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (D.R. Congo) is similarly compromised. Having temporarily lost control over half of its territory in the 1990s and early 2000s—much to forces from tiny Rwanda—D.R. Congo has again been threatened with meltdown in the last few years. Some 1.4 million of its people were forced to flee their homes in the diamond-rich Kasai region in the summer of 2017, yielding an alarming total of 3.8 million displaced persons in the country as a whole. Kasai continues to suffer from the so-called Kamwina Nsapu Rebellion, marked by campaigns of ethnic cleansing. Throughout eastern D.R. Congo, ethnic violence and warlord-led resource conflicts remain rife. In the first seven months of 2019, this region experienced more than 200 attacks against clinics and health workers struggling against Ebola.

Better known to most Americans is the armed conflict in the adjoining state of South Sudan, which was granted independence in 2011. Split between the closely related Dinka and Nuer peoples, South Sudan has been so plagued by ethnic conflicts that it ranked in 2018 as the world's most fragile state. In the area where it converges with the C.A.R. and the D.R. Congo, so little formal governmental authority is exercised that the infamous warlord Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord's Resistance Army, has been able to shelter there for years, protected by as few as 100 soldiers. Here is a stark case of what Ashraf Ghani and Clare Lockhart call the "sovereignty gap": "the disjunction between the de jure assumption that all states are 'sovereign' regardless of their performance in practice—and the de facto reality that many are malfunctioning or collapsed states..."

If collapsing states and compromised sovereignty constitute one set of problems, another set of slippages between the map and the world arise from the former's ascription of statehood to places where sovereignty was never realized in the first place. Yemen and Somalia may now be anachronisms, but at least they were coherent states at one time. The same cannot be said for all pieces of the CIA's global jigsaw puzzle. Consider the large block of desert land southwest of Morocco that the map labels Western Sahara. Here is an odd polity whose independence was never more than a diplomatic conceit. A brief account of the tragic history of this "ghost state" might explain why such a glaring cartographic anomaly persists.

When Spain finally pulled out of Africa in 1975-1976, the phosphate-rich colony of Spanish Sahara was immediately invaded by neighboring Morocco and Mauritania; when the dust settled, almost the whole of its territory had been annexed by Morocco. The annexation was deemed illicit by the global community, however, and the CIA map to this day treats it as if it never happened. Nor is this pretense limited to American official cartography. In 1984, in protest against the Moroccan take-over, the Organization of African Unity (predecessor of the current African Union) recognized the formal independence of an entity claiming to represent Western Sahara, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) - prompting Morocco to withdraw from the organization in protest. The SADR is currently acknowledged as sovereign by more than forty U.N. members.

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic today controls a small part of Western Sahara's nominal territory. Morocco controls the rest, which it guards with a heavily fortified series of sand formations (the so-called Moroccan Western Sahara Wall, or Moroccan Berm) that snakes inside the internationally recognized border with Algeria. The zone on the far side of this berm forms something of a no-man's land under the partial control of the Polisario Front, the military wing of the SADR. Called the "Liberated Territories" by the Polisario Front and the "Buffer Zone" by the Moroccan government, this harsh inland desert is inhabited by some 35,000 people. Although its largest settlement, Tifariti, is the provisional capital of the would-be Sahrawi state, the Polisario Front is not actually based there. Instead, its physical headquarters are located outside the Western Sahara altogether, in an Algerian oasis town called Tindouf. More than 100,000 Sahrawi people now live on Algerian soil (in grim refugee camps south of Tindouf), dwarfing the population that remains in the so-called Liberated Territories.

The United Nations has long held that the problem of the Western Sahara should be solved by a referendum, allowing the people of the region to choose between independence or union with Morocco. To keep this option open, the UN has maintained a peace-keeping force there called MINURSO (United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara)... for thirty years. (Designed to be temporary, MINURSO's mandate has had to be extended more than 40 times since 1991.) Over the course of those decades, the international consensus against Morocco has frayed, dimming the prospects for eventual Sahrawi independence. In 2017 Morocco was readmitted to the African Union despite its recalcitrance on the issue. European human-rights organizations campaign against importing goods from the disputed territory, but to little effect. In early 2020, Bolivia suspended its recognition of the SADR, following the lead of 42 other countries. Even multinational companies that operate in Morocco must acknowledge that Morocco effectively controls the SADR, as McDonald's discovered to its chagrin in 2007 when it offered a "happy meal" map depicting Western Sahara as a separate country. (In 2016, a contrite McDonald's opened an outlet in Western Sahara itself, an action that some experts saw "as recognition that the disputed territory belongs to the Kingdom of Morocco.") In late 2020, the Trump administration recognized Moroccan sovereignty over the region, doing so at roughly the same time that Morocco diplomatically recognized Israel. Both Republican and Democratic foreign policy experts denounced the move as irresponsible, with John Bolton demanding that Joe Biden quickly "reverse course on Western Sahara."

Given these vexatious complications, how should Western Sahara and Morocco be mapped? There is no easy answer. Wikipedia has wisely side-stepped the challenge, acknowledging the contested nature of power in the area by setting four competing maps side by side. Needless to say, only one of the four matches the vision of the CIA.

Countries with a more corporeal history than Western Sahara can meanwhile reveal other blind spots in the geopolitical model. One concerns political taxonomy. A signal feature of the CIA map is its emphasis on national boundaries to the exclusion of all others, implying that internationally recognized states are universally the locus of political authority. Provinces, administrative divisions, and other lower levels of the political hierarchy could of course be mapped as well, but the CIA chooses not to do so. Strikingly, subdivisions of the nation are invisible not only on its global map but on its more detailed regional maps as well. Nor do they show up on the national maps in its often-cited World Factbook. By the same token, supra-state entities like ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) and the EU have no place in CIA's cartographic program. In the final analysis, it is only countries that count.

But is that really true? Consider the strange case of Belgium. Starting in 2010, the Belgian legislature went for more than a year and a half without being able to form a government. While such a hiatus is usually taken as an alarming indicator of a faltering state, this one barely raised an eyebrow in the international community, and for good reason. In practice, both Belgium's internal regions and the European Union do more governing than does its "national" government. The scare quotes here are deliberate. Belgium is not a nation strictly defined; the requisite feelings of solidarity are lacking. Former Belgian prime minister Yves Leterme once quipped that the only things common across the land were "the King, the football team, [and] some beers." Despite The Economist's retort that "unity through beer is not to be dismissed out of hand," this is not much on which to ground a nation. The anti-EU British firebrand Nigel Farage went so far as to call Belgium "pretty much a non-country."

Beneath Farage's mind-boggling rudeness is a kernel of truth. Compared with the U.K., Belgium emerged as an independent state in recent times—and largely as a matter of diplomatic convenience. A piece of the late-medieval realm of Burgundy, it passed to the Spanish crown through marriage and inheritance and was later yielded to Austria after the War of Spanish Secession, only to be conquered and annexed by France in 1793. With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, its future lay in doubt. Austria had little interest in taking it back, having "learnt the hard way that isolated territories brought more trouble than revenue." Instead, the territory passed to the Netherlands. Its French-speaking elite population chafed under Dutch rule until 1830, when, with the connivance of Britain and France, a new state came into existence: one that would grow nine years later by assimilating much of Luxembourg. The new country derived its name from the ancient Belgae confederation, a polity that had once symbolized all of the Low Countries under the guise of Leo Belgicus (the Belgic Lion). The original confederation had both Celtic and Germanic components, and the new-born Belgium was similarly divided, this time between Dutch (Flemish) and French (Walloon) speaking communities (with a small German-speaking area thrown into the mix in 1920). Attempts at national consolidation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were never very successful.

Nor is Belgium the only European country where the nation-state model basically doesn't apply. Bosnia is even less cohesive. Not being a member of the EU—an entity that some regard as a "quasi-state" in its own right—Bosnia (officially Bosnia and Herzegovina) cannot rely on that robust multinational framework to shore up its legitimacy as Belgium does. Yet in some ways, Bosnia too is subject to the authority of the European Union. The most powerful official in the country may be the "High Representative" charged with representing the EU (and the larger international community) in making sure that Bosnia carries out the terms of the 1995 Dayton Accord. In practice, Bosnia functions as a single state only in the international arena. Domestically, it is split in two, divided between an autonomous Serb Republic Republika Srpska (not to be confused with the neighboring Republic of Serbia) and a troubled Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (informally called the Bosniak-Croat Federation). Viewed in this light, Bosnia is more a de jure than a de facto country, one held together largely by the insistence of the international community. An accurate political map would show its federal divisions.

So far we have looked at cases where the CIA map persists in representing lapsed, divided, or phantom nation-states. Another way that is misleads is by not representing a class of functional states: those whose existence is officially denied by the international community. Such polities have been called "de facto states" by Scott Pegg, who deems them the "flip side of the quasi-state coin."

Perhaps the clearest example of a de facto state that is consistently left off the map is Somaliland, a breakaway polity that proclaimed its independence from a disintegrating Somalia in 1991. In the decades since then, Somaliland has attained all the essential attributes of sovereignty except international recognition. Remarkably, it has been described as the most stable and best governed country in the Horn of Africa. Nor has this gone unnoticed. Israel, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) come close to treating Somaliland as a sovereign state, while Djibouti, Turkey, and Denmark maintain consulates or their equivalent in the country. Wales has even awarded it full acknowledgement. The UAE, in return for being allowed to establish a naval base, has gone so far as to promise to "protect the Republic of Somaliland from all external threats and protect Somaliland's sovereignty and territorial integrity," wording that echoes many declarations of formal recognition. The African Union, by contrast, vociferously rejects Somaliland's claims. The resistance is understandable. Acknowledging any breakaway polity could encourage similar developments elsewhere in the volatile region.

While Somaliland may be a particularly clear example of the cartographically invisible states, it is by no means the only one. The most important of these, Taiwan, is also the most complicated and will be examined below. The others all have powerful patrons, whom they effectively serve as clients. An extreme example is the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, a self-ruling entity that enjoys the recognition of exactly one UN member: Turkey. (Not surprisingly, it is often regarded as a Turkish puppet, especially in Greece.) But several autonomous zones of the former Soviet Union operate in a similar gray area, enjoying some diplomatic recognition while arguably lacking full independence. Abkhazia and South Ossetia, for example, are militarily and diplomatically supported by Russia and officially recognized by Venezuela, Nicaragua, Syria, and Nauru. Transnistria—a self-declared sliver of a state sandwiched between Ukraine and Moldova—has a more shadowy existence. With an economy based heavily on smuggling and weapons manufacturing, it is sometimes regarded as little more than gangster turf. Transnistria relies on Moscow to maintain its autonomy. Nagorno-Karabakh, in the Caucasus, is comparably dependent on Armenia. Despite having proclaimed independence as the Republic of Artsakh (an entity recognized by nine U.S. states, if not by Washington DC), its citizens still use Armenian passports.

Rebuffed by the global community, these four post-Soviet breakaways have responded by creating their own "international" organization, the ambitiously named Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations (a.k.a. the Commonwealth of Unrecognized States). Diplomats from Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and Nagorno-Karabakh have met periodically under its auspices, as if in pantomime of the United Nations. They have not yet been joined by representatives from the two newest self-declared states in the region, the Donetsk and Luhansk Peoples' Republics, whose leaders would like to merge their statelets to form something they call the Federation of Novorossiya ("New Russia"). Regarded as terrorist organizations by Kiev, both of these "republics" were hived off of eastern Ukraine in 2014 by Russia-oriented separatists, aided by the Russian military.

Whatever one makes of these splinter polities, their existence makes one thing clear: not all of the internationally recognized states that emerged out of the Soviet Union fully control the territories ascribed to them by the standard map. Unable to prevent the break-out of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, and Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh), the "parent" republics of Georgia, Moldova, and Azerbaijan have never exercised authority across their full official expanses. Immediately on gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, all of these fledgling countries saw border-altering struggles. While commonly deemed frozen conflicts, they occasionally burst into bloodshed. Azerbaijan engaged in an inconclusive four-day struggle against Armenia and its client state of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) in 2016, and triumphed against them in a much more deadly war in 2020. After the latter struggle, Azerbaijan reclaimed most of the territory that it lost to Armenia when the Soviet Union disintegrated. But since they are judged illegitimate, the resulting territorial adjustments—like the more recent Russian annexation of Crimea—go unmarked on the CIA's political map. What is frozen would seem to be the map, not the conflicts.

While the moral logic behind this refusal of diplomatic recognition is understandable, the public still needs some way to keep track of whose boots are actually on the ground. Some of these unrecognized states have endured for decades and may well persist for decades to come. For the CIA map to be truthful, it should come with the caveat that it represents an idea of the world: a vision rooted in the world-order from the last century.

Breakaway countries are by no means the only areas of contested sovereignty in the world today. Boundary disagreements are rife, involving many UN members in slow-burning conflicts. According to Alexander C. Diener and Joshua Hagen, of the roughly 300 contiguous international land borders, fully one-third are contested. Island disputes can be especially complicated, involving multiple states that are not necessarily adjacent to the contested sites. Most notorious is the Spratly archipelago in the South China Sea, parts of which are claimed by no fewer than six countries: China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and the Philippines. Labeling all of these overlapping claims on a world map would certainly be challenging. The CIA's approach is to leave the archipelago geopolitically unmarked, even though some of these islands now bristle with armaments. While one can be sympathetic with the difficulty of marking specks in the sea, ignoring land-border disputes is harder to justify. Particularly where one or another disputant insists that all third-party maps must reflect its own version of the truth, persistent boundary disputes between UN members would seem to deserve some sort of acknowledgement.

Kashmir is an instructive case. The greater Kashmir region has been contested for decades between three nuclear powers: India, Pakistan, and China. India is so insistent on controlling the narrative that it has outlawed maps that depict the actual situation on the ground, requiring cartographers to portray Pakistani- and Chinese-controlled areas as if they were part of India. CIA mappers finesse this by distinguishing Indian claims from the "line of control" (with Pakistan) and the "line of actual control" (with China). The result is a rare case where contested sovereignty is rendered visible on a document that studiously ignores such conflicts wherever possible. (For a few other exceptions, see the accompanying map-video). India's eastern border conflicts with China, by contrast, are disregarded by the CIA (and indeed by almost all other world political maps), even though one of these disputes recently emerged as a military flash-point.

Pakistan is not as demanding as India about how other countries map its spatial extent. But the official Atlas of Islamic Republic of Pakistan (2012) reveals some telling departures from the international community's boundaries in the region. Predictably, this atlas portrays Pakistan as rightfully including all of greater Kashmir, albeit labeling the region "Disputed Territory." (The border with China in this region is likewise labeled "undefined.") More surprising is its portrayal of a sizable portion of neighboring Gujarat, a Hindu-majority Indian state. After the violent partition of 1947, this area—formerly ruled by the princely state of Junagadh and Manavadar—became part of the Republic of India. The Pakistani atlas suggests that its incorporation is still seen as illegitimate in Islamabad by showing much of western Gujarat as a (non-disputed!) part of Pakistan. The global political overview in the same volume seemingly portrays the same region as an independent country. In the imagination of the Pakistani cartographer, it also retains its former intricate geography, pocked with numerous exclaves and enclaves. Although these features vanished with the end of British rule, their afterlife in the Atlas recalls Junagadh's unusual shape and status as a self-governing state under the Raj.

Whether or not they are disputed, international borders also vary tremendously in their intrusiveness on the ground. The heavily armed border between North and South Korea, at one end of the spectrum, is of an entirely different order from the ethereal abstraction separating Belgium from the Netherlands. Where the Korean Peninsula is cleft by a militarily flanked four-kilometer-wide no-persons's land, a traveler in Europe's Low Countries might cross unknowingly from one state to another simply by wandering through a doorway. A naive reader of the CIA map might imagine the Korean border as the less formidable of the two, given that it is denoted by a porous-looking dashed line (a sign meant to indicate that it remains unresolved in international law.) Or consider the Canadian and Mexican borders of the United States, which appear identical on the map despite massive differences in how rigorously they are fortified and defended. The fact that virtually every international border can be depicted just like any other is among the clearest indications that the CIA's cartographic project is a normative one. A descriptive approach would call for a different set of discriminations.

Countries are generally thought of as covering contiguous territories. Yet quite a few have detached bits, or exclaves. Americans are familiar with our own overseas territories of Alaska and Hawai'i, but most seem unaware of other examples, including some of immense geopolitical import. Few U.S. college students know that a small piece of Russia, the oblast called Kaliningrad, is almost entirely surrounded by NATO and EU member countries. (The CIA map does label Kaliningrad as Russian, but it is easy to miss.) France has more numerous exclaves, and in more distant areas. Guiana, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Reunion, and Mayotte are integral departments of France, in exactly the same way that Alaska and Hawai'i are part of the United States. While its logo-map in our minds may be the classical European hexagon, France today is also a South American country, a Caribbean country, an Indian Ocean country, and an African country.

Other border incongruities are strewn about the world as well. Nesting territories and seasonally fluctuating borders may have no great geopolitical import, but they challenge our models nonetheless. What should we make, for example, of Nahwa village: an exclave of the United Arab Emirates that is located in a larger exclave of Oman (Madha) that is in turn wholly surrounded by the United Arab Emirates? Or what of Belgium's 22 territories encircled by the Netherlands—the largest of which includes six Dutch enclaves within it? (The border between India and Bangladesh in the Cooch Behar area was even more involuted until it was simplified in 2015, counting one third-order enclave: a bit of India within Bangladesh within India within Bangladesh.) In another European case, involving Slovenia and Croatia, border complexities have generated a situation in which state authorities "are not entirely sure exactly where the border line is." Another form of anomaly arises where an international dividing line does not stay fixed in time. Such "moving borders" range from an ice-defined alpine boundary separating Italy from Austria—where an array of glacier-tracking devices are now needed to update international maps in real time—to Pheasant Island in the Bidasoa River, an islet that passes from Spain to France and back again every six months. The latter island has historically found a role as a neutral zone for treaty signing (the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659) and as a venue for royal marriages.

Nesting territories, like temporally fluctuating Pheasant Island, are a good example of geo-anachronisms: survivals of a pre-modern order that was built on radically different premises from the modern norm of clean-cut, stable borders. Geo-anachronism has other telltale expressions as well, especially in Europe. Small size is one. Luxemburg, at 2,586 square kilometers (999 square miles), is a seeming speck on the world map, but it in turn dwarfs Monaco, a nano-state of just two square kilometers. Andorra, San Marino, Lichtenstein, and the Vatican City all fall on the micro-state spectrum as well. A clue to the premodern origins of these polities is their limited sovereignty. The Principality of Andorra today counts two heads of state, both of whom reside elsewhere: the Spanish/Catalan bishop of Urgell, and the president of France. Much as it runs against the grain of French republicanism, Emmanuel Macron is simultaneously an elected premiere and a feudal prince, whether he wants the honor or not. Benign anomalies like this attract little media attention, and may well be dismissed as geo-curiosities. But considered alongside the quasi-states, de facto states, border disputes, fluctuations, and other incongruities discussed above, they further underscore the slippage between the map and the world.

And that's not all.

How many independent countries exist in the world? This seemingly simple question has no straight answer. In practice, sovereign status is conferred through international recognition, but there is neither a global consensus nor a single, binding institution capable of generating a definitive list of who's in and who's out. Instead, each sovereign state exercises the right to declare its own list of real and rogue nations. The CIA map—like the State Department list on which it is based—fudges this issue a bit. The 193 UN member states form its core, but two other polities, Kosovo and the Holy See (Vatican City), are included as well, for a total of 195 "independent states." An internet query will typically yield a slightly higher number, usually by adding Taiwan and Palestine. Such polities gain entry on the grounds that they are recognized as sovereign by some United Nations members. (Of course, that could also be said for Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and other places that rarely make the cut.) The most capacious roster, published on the World Population Review website, names 206 "sovereign nations" as of 2020.

It is not surprising that Kosovo is included on the CIA map, since it functions as a sovereign country and is recognized as such by the U.S. Department of State. Many other member states of the United Nations also recognize Kosovo. But China and Russia do not, effectively precluding its admission to the organization; as permanent members of the Security Council, both the PRC and the Russian Federation can veto applicant states. Russia rejects Kosovo's independence, viewing it as a wayward part of Serbia, a state that it has long diplomatically supported. As a result, UN maps to this day depict Kosovo—which has functioned as an independent state since 2008—as if it were still part of Serbia.

Taiwan is another vexing case. One might even say that the extraordinary call for "strategic ambiguity" vis-a-vis Taiwan reveals most starkly the limits of standard world maps and models. It is universally understood that the Taipei-based Republic of China (ROC) exercises sovereignty over the island of Taiwan. Yet most governments officially pretend otherwise, in deference to the vastly more powerful People's Republic of China. Those few that do not bow to the PRC must recognize Taiwan's own equally audacious counter-claim to be China's only legitimate government. The U.S. Department of State makes no bones about its position: "With the establishment of diplomatic relations with China on January 1, 1979, the U.S. Government recognized the People's Republic of China as the sole legal government of China and acknowledged the Chinese position that there is only one China and that Taiwan is part of China." The CIA world map falls in line with this declaration, representing Taiwan as though it were part of the PRC. It would be hard to find balder evidence that the map reflects a diplomatic vision of the world. Left unsaid is that Taiwan's people are embroiled in a long-running, high-stakes controversy over the status and future of their island, with the majority viewpoint gradually swinging away from a Chinese identity toward a specifically Taiwanese one.

While the Taiwanese controversy is the most dramatic, less familiar conundrums can be found farther down on any expanded country list. If the Holy See is granted sovereign-state status, one might ask, why is the "Sovereign Military Order of Malta" denied the same consideration? The Knights of Malta may not have an actual territorial domain, but the Vatican City is little more than a collection of buildings inhabited by an officially celibate population—hardly a real country either, as the term is conventionally understood. And if mutual recognition is taken to be an essential feature of sovereign statehood, what then does one make of UN members that are denied such standing by some of their UN fellows? This applies most notably to Israel, but also to Armenia and the Republic of Cyprus.

To craft one's list of countries on the basis of de facto sovereignty rather than de jure recognition would solve some of these problems, but that procedure would generate other headaches. Palestine, for one, would be excluded, since its sovereign power is limited; it does not control its airspace, waters, or entry points, and its spatially separated territories are far from united. Likewise, several full-fledged UN member-states could find their country status called into question. Notable here are the Pacific nations that operate under compacts of "free association" with the United States: the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. All three are essentially "para-countries" where the U.S. provides external security, access to a number of American domestic programs, and automatic U.S. residency rights in exchange for military concessions. In the case of the Marshall Islands—home of the strategically vital Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Test Site (the world's largest target, receiving test missiles fired from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California)—such considerations are significant indeed. New Zealand has similar arrangements with the Cook Islands and Niue. The Joint Centenary Declaration (2001) between New Zealand and the Cook Islands expressly declares the independence of the latter: "In the conduct of its foreign affairs, the Cook Islands interacts with the international community as a sovereign and independent state." Yet the Cook Islands and Niue are not reckoned as sovereign by the United States, and are marked as dependencies of New Zealand on the CIA's world political map. Few other lists of "independent countries" or "sovereign states" include them, either.

Interestingly, the United Nations does regard Cook Islands and Niue as sovereign states, officially designating them (on the UN map of "The World Today") as the world's only "Non-Member States of the United Nations." Crucial to this designation is treaty-making power. As noted on the United Nations website, "the Secretary-General, as depositary of multilateral treaties, recognized the full treaty-making capacity of the Cook Islands in 1992 and of Niue in 1994." But not all official UN maps grant them the same status. On the UN map of "The World," found in the same cartographic repository as "The World Today," the Cook Islands and Niue are unambiguously marked as falling under the control of New Zealand. Evidently, confusion over the status of these islands is widespread.

Compacts of Free Association generate local controversies as well, as they bring economic and political benefits at the price of compromised sovereignty. Tensions are particularly high in the Federated States of Micronesia, which, as its name indicates, is a relatively loose federation of four autonomous states. Many residents of the most heavily populated of these states, Chuuk (Truk), are pushing for full sovereignty. A much-delayed independence referendum is now scheduled for 2020. If it were to pass, Chuuk may seek to detach itself from the United States and instead seek close relations with China. Considering Chuuk's strategic location and superb harbor, this possibility has generated serious concern in Washington.

As this inventory reveals, getting a handle on all the subtleties of the international system is a maddening pursuit. The closer we look, the more irregularities we find. Riddled with contested boundaries and competing claims—and alive with moving borders, shared sovereignties, exclaves and enclaves, ghost states and para-countries—the political patchwork we actually inhabit is a precarious and jerry-rigged affair. Little wonder that most of these loose ends are routinely kept out of view; the sheer simplicity of the standard model is one of its main attractions. It was a clever move to create a make-believe surface where all countries are sovereign, national, and equal. But what is gained in legibility is lost when it comes to navigating the rough and tumble arena of power politics.

We now come to the most important acknowledged gap between the global model (based on theoretically equivalent national units) and the world map: the remaining colonial and post-colonial dependencies. Most of these territories are so small that they are a challenge to depict when mapping the world as a whole. The CIA cartographers resort to some serviceable if subtle expedients. Where recognized states (including the Vatican and Kosovo) are labeled in all capital letters, dependencies are not; in addition, the names of their sovereign superiors are noted (in parentheses). For example, under Greenland one finds (DENMARK); under Curacao, (NETH).

Still, one size does not necessarily fit all. One of the most stubborn challenges to accurate mapping of dependencies is the need to distinguish among the varied relationships they have with their metropoles. The situation of a U.S. commonwealth like Puerto Rico or the Northern Mariana Islands, for example, is not the same as that of an "unincorporated and unorganized territory" like American Samoa. The key variable is the degree of self-government. Although difficult to quantify, this metric matters a great deal to the United Nations, which maintains an evolving list of non-self-governing territories that are supposed to be on a trajectory toward full autonomy, independence, or union with their controlling power. Critics note that the decision to include or exclude a given dependency from the UN list reflects political considerations more than measurable self-governance (although at least it represents an attempt to draw distinctions). We take a similar tack here, cataloguing some of the inconsistencies and quirks in the way the CIA maps dependencies around the world. Close reading turns out once again to be an effective tool for exposing the unstated priorities—indeed, the worldview—of the map's creators.

Some of the world's not-quite-countries are classified vaguely by the U.S. State Department as "areas of special sovereignty." On both the State Department list and the CIA map, such places are lumped together with formal dependencies, making it difficult to differentiate the two categories. The two most prominent cases in the former category are Hong Kong and Macao—China's Special Administrative Regions (SARs)—which retain their own legal systems, immigration bureaucracies, and currencies, but fall under the sovereign sway of the People's Republic. On the CIA map, the SARs' status is clearly marked through the tag "Special Administrative Region," the only such labels on the map. These territories differ from other global dependencies in that their subordinate position derives from prior colonization by a country other than the one to which they currently belong. During the transition from one overarching sovereign (Britain/Portugal) to another (China), both were allowed to retain elements of their previous governmental apparatus. But that situation is scheduled to end in the mid-21st century, and already the SARs are being increasingly subjected to the power of Beijing. Given their liminal status, Hong Kong and Macao are perhaps best viewed as temporary quasi-countries. That said, Hong Kong appears be in the process of forging a national consciousness of its own, as seen in the heated clashes of 2014 and 2019. As for the other areas of special sovereignty recognized by the State Department, the map either leaves them off or marks them simply as dependencies. For example, while the CIA World Factbook specifies that the British military bases on Cyprus (Dhekelia and Akroteri) are areas of "special sovereignty," neither figures in the CIA's world political map.

If such special zones and dependencies generally remain hard to see on the map, they do show up on various tabulations and charts. One influential taxonomy is that of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), which provides two-letter "country codes" for all kinds of territorial entities (including some with no human inhabitants). The ISO Alpha-2 codebook reserves "GS" for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (with an estimated year-round population of 16), and "TF" for the uninhabited "French Southern Territories." In the ISO's reckoning, the globe is divided into 249 discrete, coded territories, all of which are formally classified at the same hierarchical level. Such a schema proves perfectly serviceable for the global organization of the internet, where the issue of sovereignty is moot.

Although increasingly used in pull-down menus on websites and in the flag-emojis employed in text messaging, the ISO country-classification scheme is seldom encountered in its pure form in general tabulations of geographical information. But in data tables provided by the World Bank, the IMF, and the CIA, dependencies are increasingly finding their place alongside sovereign states.

One might wonder whether dependencies are worth such extended consideration as we have given them here. After all, little attention is accorded to them in the standard world model (or in the mainstream media, for that matter). Most are treated as vanishing vestiges of bygone times—colonial holdovers fated eventually to dissolve into union with their metropoles or gain independence. In the vast literature on the British empire, the remaining territories are typically dismissed in a sentence or two. For Niall Ferguson, "The British Empire is long dead; only flotsam and jetsam now remain." One of the few popular authors who does focus on imperial remnants highlights the "lack of caring [that] seems to characterize Britain's dealings with her final imperial fragments." One could say the same of the United States, where imperial holdings have always been downplayed; those that remain constantly slip out of the national consciousness. As David Immerwahr argues in How to Hide an Empire, "One of the truly distinctive features of the United States' empire is how persistently ignored it has been."

Like Immerwahr, we believe there are good reasons not to ignore the world's dependent territories when thinking about geopolitical space. For one thing, although most are small in terms of land-area, many are situated in highly strategic places, and collectively they confer control over a vast expanse of sea-space. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of French Polynesia alone encompasses almost five million square kilometers of the Pacific Ocean. This makes a huge difference for the size of France. By conventional land-based reckoning, there are 40 countries on the planet larger than France. But if one includes maritime holdings, France jumps to the sixth position, trailing only Russia, the United States, Australia, Brazil, and Canada. Island possessions also allow metropolitan countries to project military power across much of the world. As Immerwahr bluntly puts it—tipping his hat to Ian Fleming—"islands are instruments of world domination."

Moreover, while dependencies may be remnants of an earlier order, that does not necessarily mean they are headed for extinction any time soon. On the contrary, most seem to be here to stay—often owing to the wishes of their own residents. In the ironic endgame of European imperialism, many territories that were once economically exploited are now subsidized, and their residents have no desire to be cut loose. Valuing their connections to Europe, the inhabitants of places like the Dutch Caribbean have rejected independence in repeated referenda. Of the six Dutch holdings in the area, half have opted to become "constituent countries" of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, while the rest have elected the status of "special municipality" within the same state.

To be sure, strong movements for independence have arisen in some former colonies. A secession movement in French Polynesia commands considerable support on some islands, and independence referenda in New Caledonia in 2018 and 2020 received heavy backing from the indigenous Melanesian Kanak population. Although the latter two plebiscites lacked enough support to pass, their narrow failure was due not only to the resistance of French settlers but also to the newer Polynesian and Asian communities. (Another referendum is scheduled for October 2020.) The current official designation of New Caledonia—"a sui generis collectivity"—says much about the uncertain nature of geopolitical affiliation in the remaining vestiges of Western overseas empires.

Local residents are not the only party with a vested interest in perpetuating para-states. Wealthy individuals from across the world profit from the shadowy status of dependencies like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, which enjoy British security without being subject to British corporate and tax law. The Cayman Islands, with a grand total of 57,000 residents, is home to a staggering 100,000 corporations, nearly a fifth of which are domiciled in a single five-story building called Ugland House. Vast sums of money stream through this and other non-sovereign financial centers, at great cost to the global economy. According to one 2014 report, "$7.6 trillion, or 8 percent of individual financial wealth... is held in offshore tax havens, resulting in $190 billion in lost annual tax revenue for governments." Not surprisingly, private interests have joined forces with the governments of these islands to maintain the status quo, resisting British and international efforts to reign in their shady financial practices. In short, despite their small size, dependencies play an outsized role in the global economy.

While colonial dependencies get at least a token nod on the CIA map, military bases are nowhere to be seen. It is tempting to infer that the reason bases do not appear on political maps is, well, political: would one really expect the CIA to draw attention to American military footholds around the globe? While that may well be part of the story, their omission has an inherent cartographic logic as well (borne out by its recurrence on similar maps made in other countries). If bases do not make it onto the map-key, it is partly because our standard world maps are designed to highlight sovereign entities (states), whereas military networks are typically created through contracts (leases). In traditional political theory (and neo-classical economics), states and leases are completely different classes of things; the one cannot compromise the other. If anything, the ability to enter into contracts is taken as proof of the host-country's sovereign status. In practice, of course, the relationship between long-term leases and national sovereignty is a fraught one, especially when such a relationship yokes the poor to the powerful.

Before we say more about bases, it may be worth pausing to briefly consider two other types of invisible exclaves with which they have telling similarities: foreign embassies and corporate holdings. Like bases, both of these entities typically come into being through lease agreements, and yet in practice they function as semi-sovereign exclaves of their home country. Embassies are unusual in the extent to which they advertise their foreignness: by hoisting the home country's flag over their property, stationing their own military personnel inside it, and exercising special legal rights within their walls (as the world is reminded every time a dissident or criminal flees to an embassy for refuge). Corporate exclaves, by contrast, tend not to announce their presence any more than necessary. The reason is not far to seek. Leaseholds and land purchases in poor countries, for the purpose of gaining access to agricultural or mineral resources, are often fiercely opposed by local citizens who denounce them as compromising the sovereignty of their nation. When a foreign state backs up such a move, opposition can be even more intense; China in recent years has been widely accused of neo-colonial "land grabs" in Africa. Similar arguments swirl around major infrastructural projects, whether funded by the IMF or an individual state. To be sure, opposition is never unanimous within the host countries. The governments in question generally welcome the investment, seeing it as a boost for their economies rather than as a threat to their sovereignty.

In the case of military bases, the compromises are starker. When staring down a fleet of foreign warships or a fortified encampment of alien soldiers, it is hard to argue that their presence does not impinge on local sovereignty. Denial becomes still less credible when the lease underpinning such arrangements can be revoked only if both countries agree to end it—or when the compensation is set so low that, as a point of pride, the host country never cashes the check. Unlikely though such extreme conditions may sound, both obtain in Guantanamo Bay, a nominal piece of Cuban territory that is effectively controlled by the United States. As noted by Joseph Lazar in 1968, "The legal status of Guantanamo Bay, both in international law and municipal law, is peculiar and unique." It effectively functions as an extraterritorial possession of the United States—one whose offshore location allows its infamous military prison to flout the American constitution. Yet on the CIA world map, it is indistinguishable from the rest of Cuba.

Guantanamo Bay is only the closest and most controversial of a great many overseas U.S. military bases. Although the figures vary among different sources, the number is staggering. David Vine, in Base Nation, calculates that the United States runs a total of 686 foreign base sites. While no other facility on foreign soil has the same entrenched legal status as Guantanamo Bay, these myriad territories collectively project U.S. military power over much of the world. Many scholars have argued that such a massive military-base complex constitutes the sinews of a veritable American Empire that is entirely invisible on conventional political maps. Even by more conservative definitions, the bulk of the North Pacific can be mapped as part of a greater U.S. realm, extending from the state of Hawai'i through the quasi-dependent countries under "Free Association" with the United States to culminate in the U.S. territory of Guam, almost one third of which is devoted to military bases. Some analysts would include security agreements under the same rubric. The noted Japan scholar Chalmers Johnson went so far as to argue that this hidden empire in the north Pacific ranges yet farther to the west: "the richest prize in the American empire" he argued in 2000, "is still Japan." Nor is the maritime extension of the U.S. military limited to the Pacific. The joint American-British base on Diego Garcia in the Chagos archipelago (also known as the British Indian Ocean Territory, or BIOT) projects power across the Indian Ocean and well beyond. In 2019, the International Court of Justice ruled that British sovereignty over the BIOT is unlawful, ordering that the archipelago be handed over to Mauritius, where its inhabitants were exiled in the late 1960s and early 1970s to make room for Chagos's militarization. Evidently, neither the UK nor the US has any intention of following the court's ruling.

While the United States has more foreign military bases than all other countries put together, it is not the only player in the game. The UK exercises sovereign power over its bases in Cyprus, while Russia maintains bases in Armenia and Central Asia. In 2015, Syria allowed the "free and indefinite transfer to Russia of the Khmeimim Air Base," further agreeing to give Russian military personnel "the status of immunity and extraterritoriality." Some states lease bases to more than one external power. In Tajikistan, for example, Moscow maintains the 201st Russian Military Base while India shares the Farkhor Air Base with Tajikistan's armed forces. Djibouti hosts American, French, Japanese, Italian, and Chinese military facilities, and additional countries are considering joining them. Such entrepreneurial leasing may well entangle Djibouti unfavorably in the geopolitical webs that it has woven, but it does suggest that the country is not a subject of any single imperial power.

As already noted, we are not exactly surprised that the territorial infrastructure for projecting power abroad goes unmarked on the CIA world map. On the one hand, leasehold arrangements are beyond its conceptual purview. On the other hand, depicting hundreds of military bases on a map at this scale would be daunting. That said, the call to do better is compelling. Anyone who is serious about mapping global political structures on an empirical basis needs to include military archipelagos, which surround and infiltrate sovereign states to create a powerful set of network geographies. How to capture it all is the question.

As we have sought to demonstrate, the CIA's world map is a useful but misleading document: one that foregrounds a US-centered diplomatic vision while hiding a host of inconvenient aberrations. The official map employed in the United States renders de facto states invisible, even as it makes chimerical ones look real. Yet the political and ideological presuppositions behind this cartographic strategy go unspoken, allowing viewers to be easily seduced into seeing it as an objective portrayal of the situation on the ground. To rely on the CIA world political map to guide our global understanding is to sacrifice empirical complexity in favor of a stripped-down and antiseptic model of geopolitical organization.

To be fair, asking the CIA to map the world in a less prescriptive and more descriptive way would be unrealistic. If only on practical grounds, designing a world depiction so detailed as to highlight tiny off-shore banking refuges along with scattered archipelagos of the US military would be challenging indeed. For general pedagogical purposes, a simple portrayal has much to recommend it. Properly understood, moreover, the CIA world political map is an invaluable document. The key to unlocking its value is to grasp what the Agency's cartographers are actually charged with mapping: the world as officially imagined by the US Department of State. That world-view, in turn, is embedded within a broader (although far from universal) international diplomatic consensus about how the world ought to be geopolitically structured. This is why almost all global political maps the world over have much the same appearance, deviating from each other only at the margin.

To reiterate our central claim, all of these conventional political maps are both useful and seductive. Put simply, they make the world look more orderly and stable than it is, masking a messy flux that requires careful attention. To take the map at face value is to assent that a country is a semi-natural entity—one that, whatever its current tribulations, will endure as a unified state. Underpinning that belief, in turn, is the notion that every country's inhabitants, however divided, form a singular people—a nation—whose collective will is best expressed through that state.

If this were always true, we might inhabit a peaceful planet. If all the countries of the world governed their own lands, served their own citizens, and respected each other's sovereignty, the world would probably be a more secure and wholesome place. In this sense, perhaps Somalia ought to be a nation-state. But that does not mean that it is one. If conflating "is" with "ought" can generate a kind of mindless conservatism, as David Hume warned in 1739, conflating "ought" with "is" can lead to blinding utopianism.

Yet the slippages between reality and depiction that we have highlighted thus far are relatively superficial, entailing merely the most obvious infidelities visible on the map. It is time now to turn to cases where the misalignment between the standard model of geopolitics and the actual global organization of both political power and national sentiments runs deeper.