Chapter 1: The Seductive Nation-State Model

Seduction is not necessarily a bad thing. That which is capable of seducing is by definition attractive. So it is with the standard world model. A political order based on a stable set of equivalent states, each representing its citizens and seeking to provide them with security and other benefits, is a deeply attractive prospect, whatever the countervailing draw of cosmopolitan globalism may be. Moreover, genuine progress has been made toward realizing this vision. Many countries do function more or less effectively as nation-states; not a few governments do strive to advance the well-being of their people. More important, the creation of an encompassing global community composed of such states, if only for the purpose of interceding between squabbling members and enhancing global concord, is embraced by millions as a boon for both humanity and the environment. As ineffective as the United Nations may sometimes be in practice, it would be dangerous to deny the value of its peace-keeping interventions or its rules and procedures for international engagement.

The problem lies in our tendency to mistake what is effectively a diplomatic vision for a description of reality. Having become accustomed to a fixed world map, we are ill-prepared for the anomalies of sovereignty that pop up everywhere once we look more closely. Three provisions of the standard world model in particular work together to cloud clear seeing: first, its representation of the terrestrial world as cleanly divided into a set of functionally equivalent countries; second, its erasure of virtually all polities other than those recognized as sovereign states; and third, its suggestion that all sovereign states are nation-states. The last may have caused the most mischief. Many countries are not and have never been functional nation-states. Our stubborn investment in this idea makes it ripe for abuse by tyrannical regimes, which can claim to represent the will of their "nations" simply by virtue of the model's presuppositions.

The present chapter lays out and critiques the standard global model by sampling some of the vast scholarly literature on, and exploring the historical evolution of, its key terms: nation, state, country, and sovereignty. Given the fraught nature of each of these concepts, the scholarship fairly bristles with disagreement; even a brief overview such as this one must deal with debate at every turn. Academic arguments have been relegated to the endnotes where possible, but thorny definitional thickets come with the territory. Readers who prefer to bypass this theoretical and historical groundwork are welcome to skip ahead to the next chapter.

The nation-state model is ubiquitous across the globe, employed by governments, embraced by the media, and disseminated by educational establishments. Since minor variations in this model can be found from country to country, we will provide a detailed explanation of the version used in the United States as our starting point in Chapter Two. (A supplemental analysis of the UN's model of the world can be found here in video format.) While the world political maps that reflect this model look like straightforward depictions of geopolitical reality, we argue that this global vision is more prescriptive than descriptive. It represents the world as it would be if it accorded with the norms of the international community in general, and the world-view of the U.S. foreign-relations establishment in particular.

The identification of every sovereign country as a nation-state is the cornerstone of this model. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a nation-state is simply another term for an "independent country." The full concept, however, is more specific, positing an exact correspondence between the state (i.e., an organized government exercising sovereign political power over a clearly demarcated territory) and the nation. The latter term properly refers to a group of people—"the people," in many formulations—who believe that they form a collective entity that is, or should be, represented by a sovereign government of its own. A vast body of scholarship carefully distinguishes the state from the nation. Yet this distinction is routinely ignored in public discourse. The conflation of state and nation is encoded in the very name of the United Nations, whose "nations" are often little more than aspirations. In practice, the UN is a collection of sovereign states, many of which have never rested on solid national foundations (and several of which do not even exercise effective sovereignty over their lands). The idea that all independent countries are nation-states is tenacious: so entrenched that no amount of evidence can dislodge it from our verbal and visual codes. Like the erroneous idea that medieval European thinkers viewed the world as flat, it persists despite mountains of evidence to the contrary. While ours is far from the first attempt to kill this zombie idea, it will surely not be the last.

The vexed concepts of "nation" and "nationalism" have generated massive historical debates. As Benedict Anderson wrote more than a quarter-century ago, "it is hard to think of any political phenomenon which remains so puzzling and about which there is less analytic consensus." "Primordialists" see the nation as originating in ancient kingdoms that were cemented by ethnic ties; "modernists" counter that it emerged only with the French Revolution, or even in the nineteenth century. Although the extreme primordial view is now deemed untenable by most historians, many scholars still stress the deep-seated ethnic foundations of many nations. Anthony Smith convincingly dates some national sentiments in Europe to the late fifteenth century, arguing that durable groups united by historical myths form the core populations of successful nations.

Rather than engage in this debate on conventional terms, we focus elsewhere. For even if some nations do have deep roots, the nation-state norm per se is a strikingly novel development. As Cornelia Navari notes, "it was only in 1918 that any government made being a nation-state the basic criterion of political legitimacy."

A prime test of what we might call "nation-stateness" is the effective identification of citizens with the country in which they live. Normatively, citizens will regard their nation-state as their legitimate guarantor of security, their ultimate legal arbiter, and the main vehicle for their political aspirations, regardless of whether they support its specific government and policies at any given time. Yet in practice, almost every country on earth harbors significant groups of people who deny their state's legitimacy, reject its demands on their loyalty, and claim to belong to a different nation that lies within or beyond their state's boundaries. Rarely are such claims recognized officially; Bolivia is exceptional in having constitutionally declared itself to be a plurinational state. In this view, Bolivia's Spanish-mother-tongue population is seen as forming one nation—sometimes called the "Camba nation" by separatists in the eastern lowlands—whereas the peoples who speak Quechua, Aymara, and other indigenous tongues constitute separate nations of their own within the same country. Following this logic, the Bolivian constitution lists no fewer than 36 official languages (including several that have gone extinct.)

Bolivia's official embrace of plurinationalism is recent and insecure, reflecting the newfound political power of its historically marginalized indigenous majority. But Bolivia is hardly alone in encompassing multiple nations within its borders. According to one Wikipedia article, 17 of the world's countries are multinational states. This list could easily be lengthened, since virtually every member of the United Nations contains populations that claim to form nations in their own right. Even the United States, with its dozens of recognized indigenous nations, does not qualify as a nation-state in the strictest sense. How exactly should we understand nation-stateness in such a context?

One way to resolve this quandary is to accept that "nationhood" can coalesce at more than one spatial level. As Guntram Herb and David Kaplan elaborate, identity takes shape at multiple scales. A person can readily identify with both an ethnic nation (say, Catalunya) and a political-territorial nation (Spain). Yet national identities at different scales do not always cohabit benignly. Most Catalan nationalists, for example, take umbrage at the idea that they also belong to the Spanish nation. By the same token, state authorities often object to the use of overtly national terminology by restive groups. The Catalans are not constitutionally allowed to define themselves as a full-fledged nacion, being permitted to refer to themselves only as a nacionalidad (nationality). In a word, the concept of the nation, in political practice if not in scholarly discourse, tends toward exclusivity. While individuals might embrace several national identities at once, states typically seek more rigid formulae, effectively making people pick a side. When Gavin Newsom, governor of California, declared his state to be a nation-state in the midst of Covid-19-related tussles with the federal government in early 2020, bemusement was the main reaction. Newsom was soon forced to admit that his pronouncement was not meant to be taken literally but was a rhetorical flourish, meant to convey "a sense of [California's] scale and scope."

A more productive way to approach this question may be to adopt a historical vantage point, viewing the geopolitical order as a continual work-in-progress. The nation-state is often contrasted with earlier forms of political organization that were meant to vanish from the map with the transition to modernity: tribal associations, city-states, city leagues, confederations, multinational empires, and so on. Yet some of these alternative arrangements linger on in important ways. What is Singapore if not a city-state? That it also functions as an effective nation-state only shows that these categories are not mutually exclusive, defined as they are on different grounds (territorial scope, in the case of the city-state, and common identity in that of the nation-state). At the other end of the spectrum are the remnants of the great early modern empires. The world's largest country, Russia, is explicitly structured as a multinational federation, as reflected in its official name: the Russian Federation. Yet according to Christopher Coker, Russia actually forms a "civilizational state," as does China, based on their own official rhetoric. Both Russia and China are heirs to early modern empires and can be viewed as functioning even today in an imperial manner—but so too can France and the United States. It is difficult to square the position of such an entity as American Samoa—officially an "unincorporated and unorganized U.S. territory"—in the nation-state model; the best way to make sense of this "anomaly" is to acknowledge it as an enduring remnant of empire.

If, as these examples suggest, the nation-state is better understood as an aspirational norm or work in progress than an accomplished fact, it behooves us to consider where that norm came from and how it caught on. Europe was clearly the origin point. The ethno-linguistic concept of the nation is generally thought to have originated with the works of Johann Gottfried Herder in the late eighteenth century. Herder conceptualized the nation in cultural terms, but his followers would soon politicize the concept. Their "state-seeking" construction of the nation gained initial traction during the Napoleonic turmoil in the early nineteenth century and found partial realization with the unification of Italy and Germany in the 1860s and 1870s. Over the same period, an alternative national ideal emerged, taking the French Revolution as its touchtone. In this version, "the people" of any given state, regardless of ethnic considerations, should band together in solidarity in order to realize self-governance. Such "civic nationalism" applied most readily to western European countries and their colonies in the Americas that were characterized by relatively low levels of ethnolinguistic diversity. In the more multinational empires of the Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman dynasties, in contrast, ethno-national separatists increasingly agitated to create new states of their own.

The resulting ethno-nationalist projects took considerable intellectual effort. Folk songs and tales were assiduously gathered, historical narratives elaborately crafted. Most people had to be explicitly taught to see themselves as members of an ethnic nation. Even in the face of such efforts, resistance—and apathy—remained widespread. As Tara Zaha documents in her fascinating study of "national indifference" in the Czech-German borderlands, as late as the 1920s, both Czech- and German-speaking parents often sent their children to families that spoke the other language to ensure that they achieved full bilingualism. Nationalist stalwarts railed against such practices, arguing that they amounted to the "kidnapping of the nation." According to such activists, children belonged more properly to the national community than to their own families. In the end, the "problem" of ethnic plurality along these borderlands was "solved" only through the mass expulsion of Germans after World War II.

Despite such misgivings and resistance on the ground, the varied strands of nationalist thought spread rapidly outside of Europe. Japanese leaders in particular eagerly embraced the nation-state ideal as part of a package of Western-derived political ideas and practices after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. In Latin America, the spread of commercial printing and the intensification of government-sponsored education nurtured the development of national sentiments in the non-ethnically based states that had emerged out of anti-colonial revolutions of the early nineteenth century.

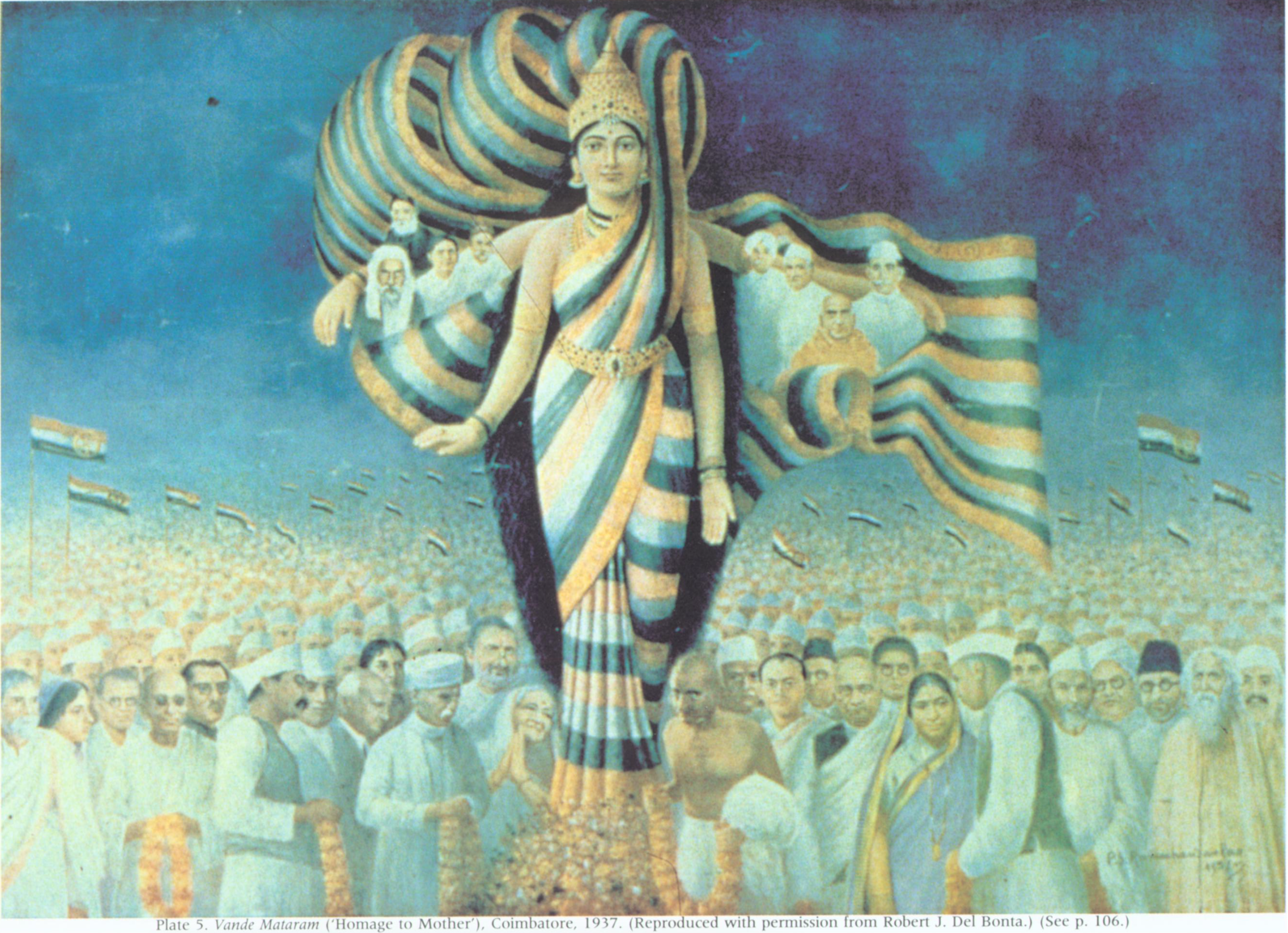

Gaining momentum at the turn of the twentieth century, the nation-state dream caught fire in one anti-imperial movement after another. The post-WWI settlement, Erez Manela's "Wilsonian Moment," marked the intellectual high point of ethnic nationalism. But the simultaneous "Leninist Moment" had related effects. In the interwar years, self-determination for hitherto stateless ethno-nations became the watchword of the day. As Wesley J. Reisser puts it, "The imperial state model prevailed prior to World War I, but following the war, the concept of the nation-state... dominated." This process entailed an intensive and hotly contested use of ethnographic maps. The new international order, as overtly framed by the leaders of the newly founded League of Nations, would be one of self-conscious, territorially-expressed nations linked together in international cooperation.

Such rhetoric obscured deeper contradictions. The most prominent European members in the League of Nations were also imperial states, with extensive—and indeed newly enhanced—overseas holdings. Most Western writers simply ignored this inconvenient detail, to the extent of arguing that only European states, along with their North and South American off-shoots and a few modernizing Asian countries, were even worthy of self-government. In practice, limitations were even placed on a number of aspiring European nations. Some were regarded as too small to form viable states; geopolitics trumped language in the drawing of some new boundaries; and a few defeated states (Hungary in particular) were territorially punished, losing much of their ethnonational lands to neighboring countries. Beyond that, the omnipresent mixing of ethnic groups across the European heartland—where urban enclaves often differed markedly from their rural neighbors—made the delineation of truly ethno-national states well-nigh impossible.

A quarter-century later, the post-WWII settlement was of a subtly different nature. The League was dead, but a similarly constituted enterprise, the United Nations, emerged under the auspices of the United States. This time, ethno-national considerations were quietly downplayed. In the redrafting of the map of Europe in 1945, most new borders were baldly based on geopolitical calculations, territorially rewarding the victorious Soviet Union at the expense of a vanquished Germany. In this geopolitical re-engineering, ethnic considerations were secondary.

Such realpolitik did not mean that the nation-state ideal was abandoned. On the contrary, it was now globalized explosively. Well before the war, anti-imperial activists had embraced national self-determination. Rather than seeking to create new ethno-states based on linguistic commonality or other cultural characteristics, however, they usually turned whole colonies (or their major subdivisions) into independent countries. Even where imperial boundaries were denounced as artificial lines imposed from afar on the colonized world, erasing them altogether in favor of a more authentic alternative would have been protracted and dangerous. Instead, most of the new countries appearing on the map between 1946 and 1975 were constructed on the basis of colonial geography. The fact that a state like Nigeria had no indigenous historical grounding did not mean that it could not turn itself into an effective nation. Doing so, however, would take serious work.

The post-war anti-colonial movement was initially resisted by the newly formed United Nations. According to Mark Mazower, the UN "started out as a mechanism for defending and adapting empires to an increasingly nationalist age." But in the Cold War context, Western colonialism was no longer strategically justifiable. Nor was it always financially advantageous. For all these reasons, the UN soon morphed into a "global club of national states." In the process, the nation-state construct lost its ethno-national moorings and had to be quietly redefined. In the post-war era, a nation-state would be any country that claimed to represent all of its people and offered to govern its citizens on an equal basis. Since every sovereign state made this claim, the nation-state idea was effectively universalized.

The dismantling of Western overseas empires thus produced an array of new self-styled nation-states. Those without indigenous foundations were expected to "build" their nations by convincing their citizens that they formed a single people who should cooperate for the common good. Some degree of national solidarity could quickly be generated across ethnic lines through mass education, political organization, and the media, leading enthusiasts to conclude that every independent country was transforming itself into a fully-fledged nation-state. By the 1970s, mainstream scholars, journalists, and politicians alike tacitly concurred that the process was a foregone conclusion, if not already essentially complete. In the process, nation building lost its original meaning, devolving from a political identity project into an institutional one, occasionally reduced to little more than the pouring of concrete. Yet enough of its original aura remains that the mantra of "nation building" has repeatedly been invoked during recent attempts at regime-change.

The end of the Cold War, and the rapid fragmentation of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia that followed, refocused scholarly attention on national cohesion in multi-ethnic countries. What had seemed reasonably solid if youthful nation-states were revealed to have been rather hollow, with horrifying consequences in the case of Yugoslavia. Ethno-nationalism, which had been essentially relegated to the past, proved itself more potent than the diplomatic imagination allowed. By 1996 Martijn Roessingh could write, "There is now, of course, a growing awareness that the tension between territorial integrity of states and the right of people to self-determination will continue to haunt the international community." Such "haunting" has hardly diminished in the decades since these prophetic words were pronounced.

Yet the notion of the national state holds its grip today as firmly as ever on the public imagination. The hybrid formula "nation-state" has surged in popularity over the past century. Rarely deployed before 1910, its use grew around the end of World War I and then rose precipitously with the conclusion of the Cold War. Today, it is all but ubiquitous, applied automatically to any state that gains formal independence. South Sudan, for example, was widely regarded as a genuine nation as soon as it became independent in 2011. Yet a mere two years later, the country almost collapsed. (As Rory Stewart notes with understatement, "U.S. intelligence was surprised... when the South Sudanese president, Salva Kiir, declared war on the vice-president, Riek Machar, and killed thousands of civilians from Machar's ethnic group, the Nuer, in a single night." )

If "state" and "nation" are the heavy-weight terms of the standard geopolitical lexicon, they are joined by a fuzzier third concept, that of the "country." Where "state" calls to mind a government and "nation" evokes a people, "country" connotes a homeland. These three terms thus gesture toward different domains of analysis, concerned respectively with politics, people, and place. Yet their usage patterns both differ and overlap in telling ways. For one thing, "country" always stands alone. While the term "nation-state" is commonplace, English speakers have never felt the need to coin the terms "nation-country," "state-country," or "nation-state-country." The territorial dimension of the trifecta goes unmarked. As geographer John Agnew has observed, conventional international-relations theory simply assumes that all sovereign states rule fixed and coherent territories: "country" need not be problematized, since the territorial state is "viewed as existing prior to and as a container of society."

There is an apparent logic to this way of proceeding. States without a corresponding nation certainly exist, as do nations without a corresponding state, but can a nation exist without a terrain to call its own? Surprisingly, the answer is yes—if we consider "nation" in the broadest sense. Historically speaking, Jews were often viewed as constituting a nation well before their claim on the land of Israel/Palestine gained traction through the Zionist movement. In the Soviet Union, Jews were explicitly designated as forming a nation; to this day, a Russian-speaking Jew born in Russia is not counted as Russian ("russkie") in the ethnonational sense of the word. But since the Leninist theory of nationality demanded a homeland for each nation in the union, the dispersed nature of the Jewish community presented a problem. The Politburo's solution was to designate a Jewish autonomous oblast, Birodidzhan, in far eastern Siberia, thousands of miles from where most Jews lived. Evidence indicates that, on the eve of his death, Stalin was planning to deport the entire Soviet Jewish population to this grim Siberian outpost, a process that would have undoubtedly been catastrophic.

But if a nation can exist without a corresponding country, what about a state? For political scientists, the answer is no; a state must have a "defined and delimited territory," as well as permanently rooted institutions of authority. Anthropologists, by contrast, define the state more broadly, as does Wikipedia, which tells us that a state is simply "any politically organized community living under a single system of government." As historians, we are drawn to Charles Maier's developmental perspective, which deems tribal polities as states of a sort while allowing that the fully modern state—his "Leviathan 2.0"—did not begin to emerge until the mid-nineteenth century.

Using this lens, one can identify numerous examples of temporarily landless states: self-governing societies that uprooted themselves at some point and migrated as cohesive groups over hundreds or even thousands of miles. This phenomenon was not unusual in Europe during the so-called Völkerwanderung from late antiquity to the early medieval period, when organized groups (often multiethnic) violently pushed into the lands of what had been the Roman Empire. The last major migration of this kind was that of the Magyars in the ninth century. For many decades, until they reached the Danube basin, the Magyars had no lasting association with any particular territory. Nor were large-scale movements of organized groups limited to the distant past. In 1618, the ancestors of the Mongolic Kalmyk people abandoned their homeland in Central Asia and fought their way across the steppe before settling down in a new territory near the northwestern shores of the Caspian Sea in European Russia. A century and a half later, more than half of their descendants returned en masse to their original homeland. Those who remained enjoy limited national self-governance through their own internal Russian republic. And as late as the nineteenth century, the Lakota nation of central North America, recognized by cultural historians as a state, transplanted itself hundreds of miles to the west. Many indigenous North American nations—including the Lakota themselves—had been making similar moves for centuries.

Mobile states (or state-like entities), such as that of the ninth-century Magyars, are a rather special case, as their mobility was temporary. Eurasian steppe peoples usually maintained mobile states on a more enduring basis, creating polities whose centers shifted with the seasons, whose boundaries were generally fluid, and whose core lands were not infrequently abandoned for new territories as they pushed each other around on the steppe chessboard of power politics.

Unfortunately, conventional scholarship has often exaggerated such fluidity, downplaying the significance of steppe political organization, even to the extent of denying the existence of true statehood across the great Eurasian grasslands. Instead, pastoral societies have often been viewed as mere tribal aggregations held together by kinship, which were only occasionally forged into powerful polities by charismatic and militarily successful leaders such as Genghis Khan. In this view, only densely populated agricultural lands can produce the surpluses and complex division of labor necessary to support genuine states.

This hoary interpretation of steppe politics, however, is currently being overturned by such scholars as David Sneath, Christopher Atwood, and Lkhamsurmen Munkh-Erdene, who convincingly argue that medieval and early modern pastoral states of Central Asia were not only militarily strong but were also tightly organized through hereditary administrative structures. These enduring institutional arrangements had their own territorial reflections, although they did not constitute territorial states in the contemporary sense. The numerically based hierarchical administration of Central Asian states facilitated the chain of command, thus enhancing the power of their leaders. These political features, combined with the military might of their cavalry forces, allowed states of the steppe to repeatedly conquer and then rule vastly more populous sedentary societies. This process arguably formed the central dynamic in Eurasian political history before the eighteenth century (barring such peripheral areas as Europe, Japan, and Southeast Asia).

Other forms of substantially non-territorialized states are omnipresent in the historical record. In many settled agrarian societies, most notably those of Southeast Asia, power gradually declined with distance from the royal core, eventually overlapping with other spheres of influence (as described in the so-called mandala model of political organization). The effective areal bases of most premodern European states were far from fixed, fluctuating from one decade to the next as a result of military success or defeat or the rewarding or revoking of loyalty to the crown by powerful underlings. Even more important were dynastic politics: the marriage arrangements and inheritance vicissitudes of their ruling families. In India, premodern ruling dynasties were if anything less firmly associated with stable territorial bases than were their counterparts in Europe. Finally, premodern European states focused their claims to sovereignty as much over individuals as over lands, as formalized under the doctrine of "personal jurisdiction." Feudal arrangements linked lords to their vassals in a fundamentally personal manner, and they persisted well into early modern times. All these governments still cared about the lands over which they exercised power, to be sure. But they did not form countries in the modern sense of the term, where the state is identified first and foremost with the territory under its control.

The emergence of the territorial state, like the nation that it came to be associated with, was a gradual process. As Jordan Branch shows, the concept of such a state—and its cartographic representation—preceded its actualization by several centuries. As early as the sixteenth century, mapmakers depicted countries or states (some of which, like Italy, had no political meaning) as neatly divided, continuous spatial units. They did so largely for practical and aesthetic reasons. Mapping the extraordinarily intricate geopolitical arrangements of the time would have been all but impossible, whereas outlining and then coloring in such "countries" was relatively simple. This process also yielded pleasing depictions with commercial appeal. The idealized territorial state was thus planted in the public imagination, and would eventually be seized on by rationalizing and centralizing political actors. But it was not until the post-Napoleonic settlement of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Branch argues, that the territorialized state emerged as the European diplomatic norm.

Branch does not claim that mapping made the modern territorial state, only that it contributed to its development. Obstacles both practical and conceptual long thwarted its realization in Europe. In the Americas, by contrast, European imperial powers overwhelmed and eventually largely erased indigenous political geography, allowing them to use this "New World" as a laboratory for rationalized geopolitical organization. As Branch writes, "It was only after the geometric view of space had been imposed and established in the New World that the same conception came to be applied to the European continent, homogenizing that space as well." But even over most of the Americas, such territorialization was long more notional than actual. The imperial powers might cartographically divide the continents among themselves, but powerful indigenous polities remained ensconced in many areas. As late as the mid-nineteenth century, the Comanche Empire (as it is called by Pekka Hämäläinen) made a mockery of national land claims on either side of the U.S.-Mexico border—claims that were etched on almost every map.

Although the European state system had been deeply territorialized by the early nineteenth century, the linkage between region and rule remained far from complete. In the era of high imperialism, powerful countries burst their territorial bounds across the globe. This was more than a matter of seizing colonies, bullying local rulers into granting "protectorates," and divvying up spheres of influence. The imposition of "extraterritoriality" on China and other weakened states by European imperial powers, for instance, effectively extended sovereign authority over European citizens regardless of where they happened to be. As Pär Cassel explains, "The foreigner not only carried his own laws and institutions into the host country, but the nebulous idea of 'foreign interests' meant that almost anything a foreigner was involved with had an extraterritorial aspect." Echoes of this much-loathed system linger on in the special status accorded to diplomats, who partially remain under the authority of their own states while living in others. Some contemporary governments, moreover, insist on their right to control their citizens' behavior even when they are abroad. Seoul has recently informed South Koreans that they cannot consume cannabis even if they find themselves in a jurisdiction where it is legal.

But if the actual linkage between state and territory is incomplete, the imagined connection has been deeply inscribed. In the public imagination, a country is the territory. The map has become a logo, instantly recognizable and emotionally charged. Even trivial threats to the shape of that logo provoke "cartographic anxieties," underpinning geopolitical tensions the world over. As Franck Billé explains, cartographic anxiety arises wherever there is a "perceived misalignment between a political imagination of separateness and the reality of a cultural, ethnic, and economic continuum on the ground." As we will see in the next chapter, such a misalignment challenges on every front the standard world model of a global community composed of individual nation-states.

To be elevated to the highest level of the political hierarchy, the nation/state/country must be endowed with sovereignty, another keyword in the geopolitical lexicon. This may be the slipperiest and subtlest term of all. The modern concept of sovereignty dates to the prescriptive works of the French jurist Jean Bodin in the sixteenth century. Worried that religious unrest was threatening the French monarchy, Bodin held that the state should be supreme, indivisible, and unlimited in time, subject to no authority other than God and natural law. In doing so, he argued against claims of supremacy by both the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) and the papacy at a time when France was extending its power over areas historically linked to the HRE. Bodin thus sought to erase the complex, hierarchical, and parcelized forms of sovereignty that had characterized medieval Europe and replace them with unitary rule. His idealized schema foreshadowed the present-day model of geopolitical organization under review in this work.

Today, sovereignty is essentially a legal construct that tightly binds territory to state power. But as Stephen Krasner and others have noted, sovereignty actually encapsulates a number of distinct phenomena. When it comes to putative nation-states, sovereignty is conventionally imagined as absolute, allowing no imposition of authority by any other power. But in practice, sovereignty can be partitioned, with different powers delegated up and down the spatial hierarchy. In the United States, the fifty constituent states and the officially recognized Native American nations routinely proclaim their own sovereignty. In Europe, the EU exercises at a supranational level many of the sovereign powers that we normally associate with the (nation-) state. As it turns out, the concept of "sovereignty," like "nation," "state," and "country," can inhere simultaneously in different levels of the geopolitical order.

Regardless of its aims, the doctrine of sovereignty has never fully prevented strong countries—or international bodies—from impinging on the domestic policies of less powerful states. Currently, impositions on national sovereignty seem to be on the rise, owing both to globalization and concerns over human rights and environmental despoliation. Such unwanted interference has led Chinese leaders to call for an international recommitment to non-intervention, sometimes framed as an "Eastphalian" rejoinder to the traditional Westphalian construct of sovereignty. But as the PRC's power grows, concern over its own interference in other countries, particularly Australia, has correspondingly mounted. Nor is China alone in this regard. Other powerful countries have long routinely engaged in such behavior, as the history of U.S. political interventions in the Caribbean and Central America so clearly demonstrates. Currently, U.S. immigration policy, aimed at keeping undocumented Central Americans out of the United States, has been described as resulting in the "erosion of Mexico's sovereign immigration control."

The conflicted nature of sovereignty derives in part from its legal development in Europe having occurred in concert with the political evolution of the territorial state. The doctrine of sovereignty theoretically enhanced state power domestically while restricting it in the international arena by limiting cross-border interference. But as the boundaries of ethno-nationally identified states in Europe rarely coincided with those of the ethnolinguistic communities they ostensibly represented, thorny complications simmered from the start. As James Sheehan notes, "the association of sovereignty and national self-determination was a constant source of unrest and often of violence."

The conflicted nature of sovereignty in the United States, on the other hand, derives in part from the country's origin in a cluster of separate colonies. As Timothy Zick explains, after the framers of the Constitution borrowed the ideas of "state" and "sovereignty" from Europe, "they proceeded to alter the concepts, first by binding states together in union, and then substantially limiting not only their powers, but those of the central government as well." Originally constituted almost as a confederation of separate polities, the United States eventually developed a powerful federal (central) government. But it was not until the post-Civil War era, after the southern confederation had been defeated, that the country came to be referred to in the singular, with the earlier locution "the United States are" changing to "the United States is."

If sovereignty remained an ambiguous and contested concept for the federal state of the U.S., it was all the more problematic for the overseas imperial holdings of the leading Western powers. As Lauren Benton has deftly shown, early modern European empires were chock full of legal and spatial anomalies. "Empires did not cover space evenly but composed a fabric that was full of holes, stitched together out of pieces, a tangle of strings." Sovereignty was often a snarled mess—a far cry from the orderly illusions of most maps, political accounts, and national narratives. The same was true of many polities at the heart of Europe itself, especially before the nineteenth century. The Old Reich, or Holy Roman Empire of Central Europe, was marked by "the omnipresence of condominiums and exclaves, the limitations of the rulers' territorial superiority, [and] the frequency of overlapping and contradictory political claims." Rulers, moreover, often enjoyed different kinds of rights and powers over different domains of action in different places. Rather than being based on contiguous, cohesive, and sovereign units, argues Luca Scholz, "the polities of the early modern Empire are better understood as a system of channels, corridors and checkpoints unevenly distributed in space."

The story of geopolitical development sketched above is at odds with mainstream international relations theory, which views the modern system of sovereign states as having essentially emerged through a single European event: the forging of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. Under this settlement, which ended the brutal Thirty Years War, all (European) states were supposed to have equal standing in international law, just as each state was to have full control over its own affairs without fear of interference by any other power. Although the Westphalian thesis has long been subject to harsh criticism, it retains a strong grip on the diplomatic imagination. As Malise Ruthven frames it in his comprehensive historical atlas of diplomacy, Carving Up the Globe (2018), "The Peace of Westphalia (1648)... established the basis for the present-day international system whereby states—territorial units controlled by sovereign governments—became the primary actors in international affairs."

The actual history of state sovereignty and territorial integrity is rather more complicated. For well over a hundred years after 1648, the supposedly sovereign states that collectively made up the Holy Roman Empire included numerous Imperial Abbeys, nano-theocracies as small as a single convent with a few attached villages. Such polities, needless to say, were not fully sovereign actors in international affairs. At the opposite end of the spatial continuum were sprawling composite states, made up of separate polities sometimes linked only through the temporary "personal unions" of their shared rulers and held together largely through dynastic ties and patronage. Some of these lasted well into the nineteenth century. In conventional historical mapping, we see a few composite polities that persisted for centuries (the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), as well as others that eventually transformed into more conventional states (Spain). But some are essentially invisible, treated as if it had been clear from the start that they were temporary arrangements. How often, for example, do our maps depicting Europe from 1714 to 1837 show the United Kingdom and Hannover as one state during the 120-year period when they shared the same monarch?

Any number of examples could be found to illustrate the fluidity and complexity of composite monarchies long after Westphalia. Navarre and Neuchâtel are interesting cases in point. The important medieval Kingdom of Navarre was split in the early sixteenth century through internal dynastic disputes followed by an invasion by Castile and Aragon. Its main geobody was then annexed by Spain while its northern, trans-Pyrenees salient was linked in personal union with France. Although Lower (northern) Navarre was fully incorporated into France in 1620, the ruler of that state was still officially styled "King of France and Navarre" until the Revolution. Southern Navarre, by contrast, survived Spanish conquest as a fully autonomous polity, endowed with a quasi-constitutional legal system (fueros) until 1841. Certainly through the period of Habsburg rule (1516-1700), "Spain" was a complex, multinational, composite state in which the bounds of sovereignty were not always as clear-cut as they appear in historical atlases.

Or consider Neuchâtel. In the eighteenth century it was both a region associated with the Old Swiss Confederacy and a hereditary principality under the personal rule of the king of Prussia. It was allowed to join the Swiss Confederation in 1815, but Switzerland at the time was still a mere political association. In the revolutionary year of 1848, local republican rebels seized power in Neuchâtel just as the Swiss Confederation was being transformed into a sovereign federal state. Eight years later, an unsuccessful pro-Prussian coup tried to reestablish monarchical rule in Neuchâtel. When that failed, Berlin broke diplomatic ties with Switzerland and threatened war. As international tensions mounted, Prussia agreed to relinquish its claims to Neuchâtel, but only after its king was mollified by being allowed to keep his now merely symbolic princely title to the little realm. Needless to say, such events do not exactly illustrate the Westphalian model—based on the supremacy of the fully sovereign territorial state—in action.

As Philip Bobbitt has exhaustively demonstrated, Westphalia was merely one step in the lengthy transition from the pre-modern order of personal states, defined by allegiance to dynastic families, to the modern order of territorial states. The Peace of Westphalia was preceded by the Peace of Augsburg (1555) and followed by the equally important Treaty of Utrecht (1713) and Congress of Vienna (1814-1815). Still, the fully modern territorial state—Maier's "Leviathan 2.0"—did not crystalize until the mid-nineteenth century, with the national state only becoming the norm with the Treaty of Versailles (1919). The modern nation-state, held to be universal, did not gain center-stage until the decolonization movement shattered the global Europeans empires in the early Cold War era (1947 to 1975).

The Westphalian thesis of sovereignty looms large in the diplomatic and scholarly imaginations, informing entire schools of historical-political analysis. Like the world model that it underlies, it is seductively simple, making the sovereign state appear to be far more deeply grounded than it actually is. The standard model of international relations is based on a geopolitical structure that did not fully gel until the mid-twentieth century and was already beginning to dissolve when the millennium came to an end. It is thus hardly surprising that it fails to offer an adequate account of the world, whether in the past or today.

To be sure, the limitations of both the Westphalian model and the standard world political map that it informs have been often noted. Many scholars, in fact, throw the entire notion of national boundaries into doubt. In an era of intensifying transnational networks and relational spaces, some insist that the modernist project of dividing the globe into bounded polities is rapidly becoming obsolete. According to the popular writer Parag Khanna, the world "is graduating toward a global network civilization whose map of connective corridors will supersede traditional maps of national borders... We are moving into an era where cities will matter more than states and supply chains will be a more important source of power than militaries." As illuminating as it is, we find this thesis incomplete. Despite the undeniable rise of global networks, there is no real evidence that states are going away; on the contrary, nationalism is on the rise. Unexpected assaults on the global order, like COVID-19, can serve paradoxically to re-inscribe borders. Geographer Alexander Murphy deserves the last words here:

"Territory's allure, in short, remains a powerful force in our contemporary world of flows, relational spatial understandings, and new ways of envisioning space. Our fascination with the latter should not blind us to the power of the former."