Introduction: Where Did We Go Wrong?

The U.S.-led military incursions in Iraq and Afghanistan must surely be counted among the greatest financial miscalculations in history. The Bush administration originally estimated that the Iraq war would cost $50 to $60 billion, with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz imagining that it would pay for itself through Iraqi oil revenue. U.S. leaders also thought that the conflict would end quickly (in "weeks rather than months," prophesied vice president Dick Cheney; Rumsfeld thought that it might be settled in five days). Yet a decade later, some estimates were placing the cost in Iraq alone at over three trillion dollars, with one publication pegging it at six. In Afghanistan, the cost of the war had reportedly exceeded two trillion dollars by the time an insecure peace agreement was reached in early 2020.

To be sure, not everyone in the United States thought that installing friendly, capable, and democratic regimes in Iraq and Afghanistan would be cheap and easy. The invasion of Iraq in particular provoked widespread outrage, with many voices warning of deep troubles ahead. It is instructive to recall, however, the breadth of bipartisan support at the time, with 58 percent of Democrats in the Senate and 39 percent of those in the House of Representatives voting to authorize military force. More strikingly, the September 2001 congressional authorization for the Afghanistan war received only a single dissenting vote. If Congress had had an inkling of how much their decisions would cost the U.S. treasury, of how large the body count would be, and of how little stability would be generated after years of conflict, it seems doubtful that either measure would have passed so handily. A decade and a half after the initial authorization vote, even many Republicans had come to the reluctant conclusion that congresswoman Barbara Lee, reviled though she was at the time, may have been wise in rejecting the use of military force in Afghanistan.

Remarkably, the dashed hopes of the political right in Iraq were mirrored just a few years later by similarly unrealistic projections from the other end of the political spectrum, when many leftwing opponents of the Iraq war evinced their own unfounded optimism in regard to the so-called Arab Spring of 2011. In this case, it was widely imagined that popular uprisings would overthrow repressive regimes, allowing Syria, Libya, Yemen, Egypt, and other Arab countries to turn the corner toward peace, toleration, and freedom. The means were different from those pushed by aggressive regime-change advocates a decade earlier, but the endpoints were imagined in similar terms. Yet as the Arab Spring morphed into the Arab Winter, it soon became apparent that the consequences too would turn out to be similar.

Could it be that a common fallacy underlay both misunderstandings?

The central argument of this book is that such common ground does exist, and that it can be found in a fundamental misperception of what Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria actually are. According to the prevalent model of global geopolitics, these countries (like all others) are nation-states. The hyphen signals the idea that the nation, a self-conscious political community, aligns with the state, a sovereign government ruling a clearly demarcated territory. In theory, this is accepted across the political spectrum; in practice, it is only sometimes true. Over large swaths of the earth, the nation-state is more of an aspiration than a historical fact. To be sure, some nation-states are firmly established; a country like Denmark or Japan has sufficient cohesion to survive even an exceptionally severe crisis. But many, including Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, are less secure. While not lacking national foundations entirely, their nation-stateness is relatively recent and continually contested; when push comes to shove, centrifugal forces can prevail. In practical terms, viewing all countries as fundamentally the same species turns out to be a fallacy.

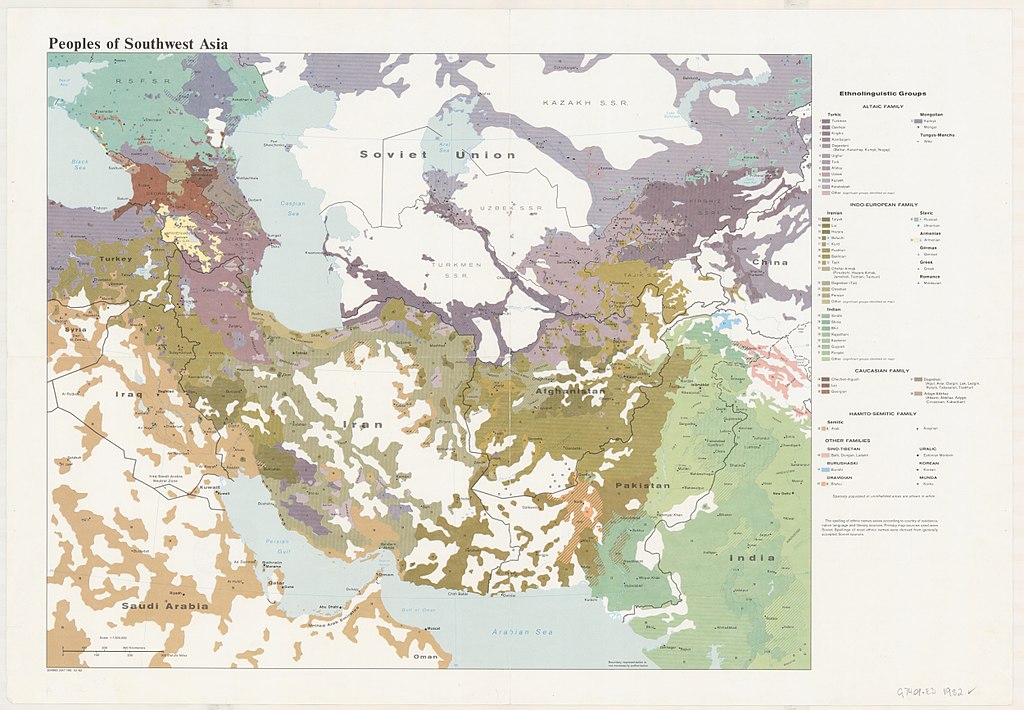

While the illusion of nation-state universality has numerous sources, one is particularly powerful: cartography. Since World War II, millions of people around the world have been exposed to one or another variant of a standardized world map, all of which operate in the same fundamental way: by portraying the globe as neatly divided into a discrete set of basic units, all of the same type. To represent the world this way—effacing the complexities and contingencies of global geopolitics—is inherent to modern mapping. As the literature in critical cartography demonstrates, political maps by their very nature generate compelling visual illusions of coherence and stability. For Denis Wood, this is their most important function: "it has been essential that states appear as facts of nature, as real enduring things, things like mountains; and at all costs to obscure their recent origins... and their tenuous holds on tomorrow." On these terms, the ubiquitous mapping of the world as a collection of stable nation-states is effectively a mirage. The resulting vision may be comforting, in its suggestion of inviolable boundaries and uncontested sovereignty. But if so, it is an illusory comfort.

What we propose here is a broader cartographic program: one capable of complicating the standard map by highlighting the ragged edges of the international system, as well as by exposing the holes and hierarchies hidden within it. Needless to say, the existing map of nation-states still has a role to play. At one level, it has value as an aspirational document. When it comes to arbitrating inter-state relations, the UN's map of the world can function somewhat like the International Declaration of Human Rights or the Kyoto Protocol on climate change: it encodes a planetary vision that, while never fully achieved, embodies many worthy and widely shared ideals. (We will say much more on this below.) At another level, the standard picture of the world has pedagogical value. It offers a useful starting place for learning about the world, as well as a handy reference point for discussion and debate.

To the extent that engagement with global affairs calls for a visual shorthand, that task is most efficiently accomplished through maps. The point is not to reify any one among them. Grasping global geopolitics at a sophisticated level means putting multiple maps in dialogue—both with other information sources and with each other. After all, no map effectively stands alone. As Matthew Edney notes, each takes shape "within a web of texts that provide the map with different shades of meaning." While official cartography offers an indispensable starting point, in other words, it is not enough; the counter-maps of anti-state movements and independent thinkers, along with evidence from archives and contemporary witnesses, are essential as well.

To associate the failed regime-change gambits in the Middle East with something as mundane as the maps on our school-house walls is admittedly a speculative exercise. The authors of this study have no privileged access to the mental constructs of war planners or popular-uprising enthusiasts, nor can we gauge the degree to which geographical ideas contributed to their miscalculations. But the purview of this book is a more general one. Its point is that the standard model of geopolitical organization (laid out in Chapter 1), like the map that both reflects and reinforces it (critiqued in Chapter 2), fails to conform to reality over much of the globe—and that the resulting slippage has real-world consequences. To the extent that this flawed model is employed to guide and inform political actions, whether consciously or not, missteps are to be expected. While there is no guarantee that better mapping would lead to better outcomes, it does seem worth a try.

The first challenge for such a project is to reckon with nationalism. If in some parts of the world most countries lack firm national foundations, in other places the veneration of the nation-state is intensifying. Ironically, while aiming to strengthen the individual state, hard-edged nationalism threatens the international system that underwrites state sovereignty in the first place. Ardent ethno-nationalists often reject existing state boundaries, demanding additional territories in order to incorporate members of their ethnic group who reside in neighboring countries. For this reason among others, the multilateral structures that lent stability to the postwar ecosystem of sovereign states are coming under increasing pressure. It is for good reason that Richard Haas contends that the world is now "in disarray," while other observers warn of a "new world disorder." The international order embodied in the standard political map shows serious signs of weakening, and it is not clear how the system will respond—or, if its center does not hold, what will replace it.

Indeed, the current revival of nationalism is roiling even the world's more coherent nation-states, prompting fears that it could rekindle international strife. The United States is hardly immune from such trends. The "America first" movement has generated a slew of soul-searching books and articles from across the political spectrum. Where some authors caution that pride and prejudice are inherent dangers in all forms of nationalist discourse, others seek to recuperate a kinder, gentler form of nationalism in the interest of socio-economic solidarity. To navigate a wise course through these debates is one more reason to scrutinize the world political map, whose basic building-blocks form both the crucibles and the targets of nationalist sentiment.

As this brief overview suggests, nationalism is an ideologically freighted phenomenon that varies widely in both form and intensity across the world. Strong nationalism might seem to arise naturally from solid national cohesion. But one does not necessarily generate the other. Iceland has been described as the world's only "perfect" nation-state, yet Icelandic nationalism has hardly been a burning force. On the other hand, as George Orwell emphasized, nationalism can be heightened through hatred of a common enemy—even (or perhaps especially) among people who have little else in the way of common bonds. Setting aside the controversies surrounding nationalism as an ideology, we will focus in the chapters that follow on various forces that appear to contribute to national cohesion. Both the strength of national identity and the subsoil that it taps into vary tremendously from one country to the next. In historical perspective, such diversity is not surprising; the 193 member states of the United Nations have strikingly different origin stories. National cohesion, state coherence, and territorial integrity in each case have distinctive local sources—which in turn provoke different responses to the mounting challenges facing the international system. For this reason above all, delving into the complex foundations of national identity is a timely exercise today.

To that end, this book offers detailed empirical discussions of political geography around the world, making arguments in cartographic as well as textual form. As noted already, we do not propose to replace the standard world political map with an alternative master-map. Instead, we will be pointing toward hundreds of cartographic resources that together illustrate circumstances on the ground in ways that no single depiction could ever capture. It is partly because reproducing images in large numbers is not feasible in book form that we have chosen to publish this work digitally. Interested readers can click on the marginal thumbnail maps to examine detailed portrayals of almost every geographical distinction and pattern mentioned in these pages. Map captions are provided in audio as well as textual format, to allow readers to keep their eyes on the image as it is being explained. Where an issue merits a more extended gloss, we have added explanatory videos. These videos allow us to highlight specific geographical features, juxtapose contrasting representations, and post map sequences, all while using audio voice-overs to explain the images at hand. These strategies also allow us to delve into the digital cartographic archive, illustrating our historical arguments with some of the thousands of images that have been made available through the Stanford University Library's David Rumsey Map Center, among other public repositories.

The digital platform of Seduced By The Map provides additional advantages, not least of which is free availability across the world for any interested readers of the English language. In time it will allow us to include critical commentary, elaborations, and suggested references from fellow scholars and other experts in the field. Finally, it facilitates serial publication, letting us post new chapters as they are completed.

This project represents a continuation of work that the authors began more than two decades ago. In The Myth of Continents: A Critique of Metageography, we examined the intellectual history and political salience of the largest partitions of the globe, focusing chiefly on continents but also exploring world regions (Latin America, East Asia, the Middle East, etc.) as well as directional divisions like East & West, North & South. In the intervening years, we have taken these concerns in different directions, investigating such issues as the division of the hydrosphere into named oceans, seas, bays, and gulfs, and the historical evolution of Japanese continental categorization. The moment now seems ripe to turn our attention to the next level down, focusing on the mapping of sovereign units in the international system. In tackling the nation-state model of the world we encounter a more complex schema—and one of much greater significance for the story of humankind. If this effort has taken a longer time and assumed a more unorthodox form than the last one, chalk it up to our attempt to come to terms with its enormous complexity.

Our views on the standard world model are informed not only by our own professional biographies but also by the intellectual environments in which we operate. If the nation-state schema retains a lock on the public imagination, its grip has loosened considerably in academic discourse. This is especially true in our own fields, history and geography. As a result, some of our colleagues may well find our central thesis unsurprising if not banal, as the nation-state no longer forms the centerpiece of their own historical mental maps. "Rescuing history from the nation," as Prasenjit Duara frames it, is by now a well-advanced project.

But it is instructive to note how recent this change has been. In 1981 (when we were students), Stanford's James Sheehan could cogently argue that "most modern history is national history"—grounded in national archives and couched in a narrative structure that takes nation-building as its telos. Sheehan demurred from this consensus. In surveying German history, he found that prior to the militarily forced unification of 1871, nothing of the sort obtained. "There was," he flatly asserted, "no terrain, no place, no region which we can call Germany."

Sheehan helped lead Stanford's history department (which we joined in 2002) in a different direction: one that stresses trans-national and global processes, as well as regional and local developments. Stanford's historians of modern Britain, France, Germany, Japan and other countries do not view these states as given and self-contained units of analysis, but rather frame them as historically generated polities that must be understood in their relationships with other places, particularly their own colonial empires. Likewise, its historians of Russia and the Russian Empire extend their inquiry westward into Central Europe, and southward as far as Afghanistan. Whether they work on the United States, Latin America, Africa, or any other part of the world, our colleagues—like their counterparts at most American universities today—generally try to transcend the national frame. In every field, there are movements toward transnational, international, and global history.

Such a change in orientation is not unique to the U.S. Across the globe, historians today often paint on a broader canvas and use more variegated hues than did their predecessors. Elsewhere in the humanities, too, novel geographical frameworks of investigation continue to emerge, each offering new insight into processes of development and patterns of exchange. Maritime basins have proven particularly attractive in recent years, and at multiple scales of analysis. Indian Ocean studies, to take just one example, is now a thriving field that is being enriched by more precisely focused inquiries, such as those of Sunil Amrith on the Bay of Bengal and Jonathan Miran on the Red Sea.

Geography has undergone a similar transformation. The American Geographical Society (AGS), a once powerful and prestigious body that helped shape the post-WWI Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920), has recently been recast as a collaborative framework for transnational, transdisciplinary work among scholars, teachers, political actors, and cartographers. Political geographers associated with the organization, including Alexander Murphy, Alexander Diener, Joshua Hagan, and David Kaplan, have come to a number of the same conclusions that we have reached in Seduced By The Map.

If the core themes of this work are thus in broad circulation, one might ask why it is necessary to elaborate them to the extent that we are doing. Our response is two-fold. First, it is one thing for historians, geographers, and political scientists to acknowledge the perplexities and perversions of an outmoded world model, and quite another for such views to seep into the public conversations where they can inform policy. Second, the standard world model and map, outmoded though they may be, have never been subjected to the kind of focused critique that we offer here. We will begin by tackling the model.